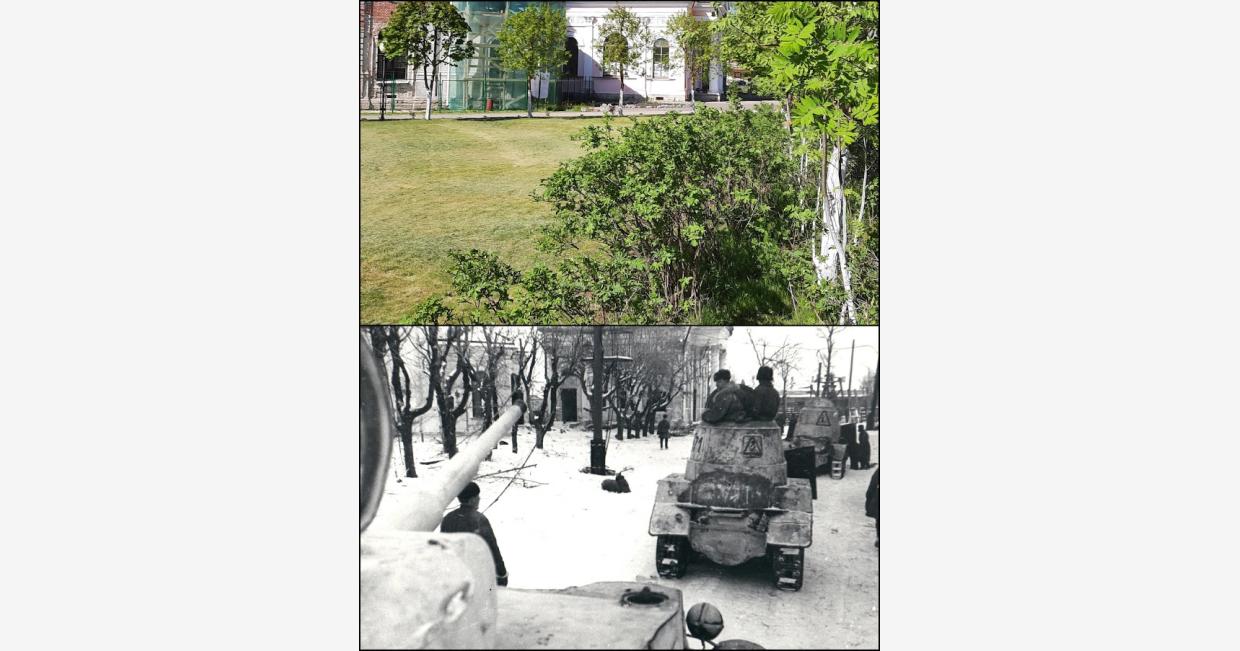

Shlisselburg, Leningrad province. January 19th, 1943 / Shlisselburg, Leningrad province. April 2019

BA-10 armoured cars of the 61st Light Tank Brigade enter Shlisselburg. The brigade showed exceptional performance during Operation Spark and in February 1943 it was reformed into the 30th Guards Tank Brigade.

Today, 80 years ago - Breakthrough of the Siege of Leningrad!

Leningraders heard this news only in the late evening of January 18th, although the troops of the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts linked up in the area of Workers' Settlements #1 and #5 before midday. Nowadays these sites are marked with memorials, but back in the day the names of these obscure places meant little to Leningraders, and the headline of the day for both newspapers and radio announcers was "Shlisselburg is ours!" It is exactly the news of the liberation of this small town, the one settlement that merited this name among the villages and hamlets in the entire liberated corridor south of the lake Ladoga, that became the victory cry. Below is an extract from the memoirs of Nikolay Vasipov who took part in the liberation of Shlisselburg in the ranks of the 34th Independent Ski Bridgade.

From the memoirs of Nikolay Khasyanovich Vasipov. Born in 1924, he took part in the storming of Shlisselburg which was his first real combat experience. His 34st Independent Ski Brigade was formed mainly from 17-18 year old boys from Leningrad who survived the first deadly winter of the Siege. After building unit cohesion and completing training in Sertolovo, just north of Leningrad, the brigade was sent to assault the German garrison of Shlisselburg which received stand fast orders from Hitler.

"On January 17th we started preparing for the storming of Shlisselburg. A foggy dawn was violated by the roar of guns, mortar crews of our battallion also opened fire at the enemy's firing positions. The groves where our skiers prepared for their decisive dash into attack were engulfed by the fiery storm unleashed by German guns. The Earth shook with the bursts of artillery shells.

The Chief of Staff Mikhail Bik gave his signal and the skiers rose at full height into attack, following their commander's example. Shouting "Hurrah!" the attackers persistently pressed the enemy, driving deeper into German defenses. The Fascists kept holding on to every dugout and every building. The skiers managed to advance rather deep into the enemy ranks, but the fascists managed to pin them down by the deadly fire of their machineguns as they laid on plain open ground. The enemy kept shooting at our lads, "groping" for them with volleys of bullets and picking them off one after another. There was nowhere to escape, and then Kalchuzhny's detachment with the machinegunner Komarov managed to outflank them by running in short spurts towards a small gully. After a few minutes, which seemed like hours to us, the Fascist machinegun went silent. Komarov and Kalchuzhny called fire on their position, which allowed the company to continue its advance. Sergeant Kalchuzhny died a hero's death in this battle, while Komarov feasted in the liberated Shlisselburg, inviting his comrades to taste some trophy honey. He didn't visit veterans' reunions after the war.

The officers of the battalion were fearless in battle, because they had to lead young recruits to recapture the historic Shlisselburg, the first town to be liberated in the area of the encircled Leningrad. In the most intense hours of fighting the Chief of Staff of the battalion Mikhail Bik, sporting a shrapnel-tattered overcoat and a submachinegun on his neck, helped our units. The situation was difficult in all sectors, but he always managed to get to the places where it was becoming catastrophic, inspiring people. It was impossible not to follow him in combat.

Back then frontline newspapers wrote about him: "Every enemy wooden bunker ceased to exist once Lieutenant Bik got to pay it a visit". The courageous officer was nicknamed the "Bane of enemy bunkers" and we believed his bravery shielded him from bullets.

All the time I knew Bik a sly smile never faded from his face. He had a rapid mincing gait, fast as a whirlwind. There was so much life in him, however one could often fear for his life while being next to him. He never took much concern for his own safety.

Early in the morning ski units broke the enemy resistance and took over the railroad embankment which led to the Workers' Settlements. Our last objective was to reach the Old Ladoga Canal. Everyone was brimming with enthusiasm to put an end to the fighting in one fell swoop. Suddenly a surviving German pillbox opened machinegun fire. The unstoppable Lieutenant Bik crawled towards it, only shouting "Cover me!" He managed to throw his handgrenades precisely in the bunker's embrasure and it was done finished off. With thunderous cries "Hurrah!" the 3rd Independent Ski Battalion led by Captain Lunin and Deputy Political Officer Pinakhin reached the canal. The 1st and the 2nd Battalions, exploiting the success of the 3rd, closed the ring of encirclement around the town... Lieutenant Bik died a hero's death near Krasny Bor in February 1943. Having heard about it, we couldn't believe that the lucky courageous Bik could have died. We got used to him being so lucky in battle. [Bik was nominated for the Hero of the Soviet Union medal but was awarded a lesser Order of the Red Banner instead. His nomination citation has the following passage: "Bik single-handedly destroyed an enemy dugout bunker with 12 men in it and 7 other wooden machine gun bunkers on the outskirts of Shlisselburg" - Alexander Shmidke]

Alexander Moiseevich Belenkin, Doctor of Philosophy in History, head of Political Department of the 34th Ski Brigade, also died during the storming of Shlisselburg. He was the heart and soul of the brigade. Belenkin earned great and heartfelt respect among the soldiers, having charming looks and charisma. During combat training he was in the thick of the action among the soldiers. He found time to look into their souls in the course of their conversations, asking them about their family matters and helping them as much as he could in that difficult time. It seemed like he found himself wearing a soldier's overcoat purely by accident, holding very humanistic views and being diversely educated. It's difficult to even describe the capacity for empathy of this modest and simple person who respected everyone's dignity. In fact, he was a seasoned commander and as a soldier I'm proud that I knew him and talked to him. War doesn't care if you're humane or not, but I think such people rarely happen to come into this world. He could have done a lot of great things for our society, but men like him just can't live without giving themselves away to the people to the last drop of their blood.

During the storming of Shlisselburg he couldn't simply sit in a reinforced dugout and in the course of the most intense fighting for the 3rd battallion he was mortally wounded in the stomach. All our men were deeply stricken by this. We all visited him at the operating table and when we realised the life of our beloved Head of the Political Department had ended we knew we would not ever never have such man in charge again, someone who could understand the needs and worries of every single soldier." [A.M. Belenkis was posthumously awarded the Order of the Red Banner - Alexander Shmidke]

During the forming of the 34th Independent Ski Brigade the enlisted personnel was selected from among the best, the most cordial commanders who were so much needed by the Leningrad boys who had to shoulder the burden of war that was way too heavy for their age. We saw so little in our lives yet the soldiers who survived the war in their trenches went through such ordeals that God forbid anyone to experience.

When the skiers of the 34th Brigade liberated Shlisselburg from the Fascists, all exhaustion and hunger, all of this immediately vanished, everything and everyone was engulfed in overwhelming jubilation.

On the streets of Shlisselburg soldiers were kissing each other, and one could thinks they were all very close friends who hadn't seen each other for a long time. Shredded snow suits were barely holding on the shoulders of many, while many others had already lost them, and there wasn't a soldier whose clothes wasn't stained by his blood or the blood of others. As it transpired later many of them didn't leave the battlefield with light injuries as each of them saw leaving his comrades unthinkable in such critical situation.

In the fighting for Shlisselburg we lost two thirds of the brigade's personnel strength as KIAs and all the rest had injuries of varying degrees. In the morning on January 19th 1943 all those who died on the battlefield were buried in a common grave in the south of the town with due military honours.

After the burial the remaining skiers were lined up and read the order of the Front Command which said about the courage displayed by the Brigade's personnel during the storming of the Shlisselburg. The meeting was attended by the member of the Military Council of the Leningrad Front General Shtykov who mentioned that the Council appealed to STAVKA to grant the Brigade the honorific Guards title. [After suffering heavy losses in the fighting near the Sinyavino Heights and Krasny Bor the brigade was disbanded on March 20, 1943 - Alexander Shmidke]

We were given a three day rest, however we never had a chance for that. In the evening we received fresh personnel to make up for the losses, and the next morning we were sent to fight in the bogs of Sinyavino. This is where I was gravely wounded on the 2nd of February.

Later this month the Brigade arrived to the village of Rybatskoye (now there's a metro station in St. Petersburg), and in March the brigade took part in the fighting around Krasny Bor.

Our unit didn't last long. It flared up like a bright torch and faded away into virgin snowland, but the young boys who took part in the liberation of Shlisselburg consider their service in it the most important time in their lives. It resounded with pride in the hearts of all its soldiers till their last days.

Although the skiers were yet to walk the long road of war, serving in many other rifle units, they had already lost their fighting comrades and sustained 2 or more injuries. According to official statistics, less than 3 percent of us, those who were born in 1924, returned from the war.

In 1965 I sent a request to radio and TV stations to help me find the surviving soldiers from my Brigade. I saw the soldiers from other units being so happy to meet each other and I thought how could it happen that all other skiers were silent, it just couldn't be they had all died.

I kept going back to what I went through in my memories and my soldier's heart was ever restless. I mentally addressed the lads who died, pleading them: "Forgive me, comrades, that I stayed alive and you didn't".

And my efforts didn't go in vain. In the past years more than 50 skiers, mainly the ones who lived in Shlisselburg and nearby, came to veterans' reunions. On May 9, 1995 on 19 skiers were present at the meeting. Many others were not able to come and regretted about this deeply in their letters, and many others had already passed away. They wanted to live to meet the anniversary of Victory with us so much, but fate passed its own judgement."

Submachinegunner of the 3rd Independent Ski Battalion of the 34th Independent Ski Brigade, Private Nikolay Khasyanovich Vasipov.