By the end of October 1941 the German Army was at the gates of Moscow, having broken several rings of Soviet defences and trapped several hundred thousand Soviet troops in encirclements. However, autumn rains which turned roads to lakes of mud and the need to improve their overstretched logistics forced the Germans to halt their operations. After a two weeks' lull in the fighting, it was the early Russian winter which afforded, contrary to popular misconceptions, the ever-vanquishing Panzers an excellent opportunity to continue their inexorable advance towards the Soviet capital. From early November to December 6 temperature fluctuated within the range from 0 to -10C, making previously muddy roads become solid with frost while being high enough not to cause hypothermia and frostbite. In mid-November the German High Command attempted to encircle Moscow from the north by going south from Kalinin, and from the south, once again trying to cut off and capture the strategically important town of Tula. As both offensives got slowed down by heavy Soviet resistance, the Germans decided to play their final gamble at the central sector of their offensive. The plan was to make the Soviet front collapse by fast tank breakthroughs from unexpected directions and minor encirclements.

Forces of the German 7th and 20th Army Corps had to strike at the troops of the Soviet 5th Army which defended the vitally important Minsk highway in a classic double envelopment move, converging upon the town of Kubinka. At the same time, in an attempt to encircle the troops of the 33rd Army, German tanks had to make a surprise dash along forest roads just north of the Kiev highway, severing both the highway and the Moscow-Naro-Fominsk railroad. This allowed them not only to sever these important logistical lines of the 33rd army, but also to threaten the entire Soviet Western sector with complete collapse. The Wehrmacht's final strategic gamble at the gates of Moscow began on December 1st, 1941.

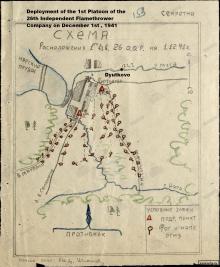

Early at dawn's break a large group of German infantry approached Dyutkovo, a small village located just 2 miles away from the Naro-Fominsk-Kubinka highway. No serious defenses were visible at a distance, and it seemed like it was going to be another routine operation. What could have alerted the attackers was the surprising absence of enemy fire as they approached the village closely. There were no signs of anti-personnel mines either. However, what awaited them was several times worse. As the soldiers approached the village closely, the earth around them became lava in the literal sense of this word. Two dozens of powerful flamethrower jets burst out of the ground, engulfing the unfortunates in sticky flaming liquid jettisoned to the distance of over 100 meters by powerful FOG-1 projecting incendiary mines. Soldiers started rolling over the snow, dropping their equipment and gear, several others ran to the nearby pond and drowned there. Having lost over 60 men, the rest of the attacking force fled, seen off by rifle and machine gun fire of Soviet infantry. Curiously enough, the German unit that attacked Dyutkovo was the only Werhmacht foreign volunteer formation which took part in the Battle of Moscow, the French collaborationist Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchévisme.

The situation at the other flank was far more dangerous for Soviet defenders. Just 2 miles (3.2km) from Dyutkovo a column of both infantry and Panzers advanced along the highway to Kubinka, reaching the village of Akulovka by noon. Upon capturing the village, it drove further along the highway. A couple of hundred meters after crossing the bridge over river Myata it met the same fate as the hapless Frenchmen. More than 20 FOG-1 mines were set off by Soviet combat engineers sitting in a camouflaged trench. Three German tanks were set ablaze and burnt down along with their crews and a platoon of infantry that escorted them along the road. Those who survived were finished off by Soviet rifle fire. However, unlike the French volunteers German soldiers did not abandon their attempts to break Soviet defenses and attacked across the field north of river Myata. As they took over several forward trenches and advanced to the rim of the forest, another set of FOG-1 mines was blown up, incinerating around 40 German soldiers. In the night the crew of disabled German tank that stopped within 20 meters from a flamethrower position got out of their vehicle in an attempt to repair it and drive back to their lines, but Soviet defenders noticed their movement and set the fuses of 4 nearby mines, roasting the tankers. Although the Germans made attempts to attack again over the course of the next 3 days, they were not able to advance any further and by December 5 the fighting in the area subsided considerably.

FOG-1 flamethrower mines were introduced to the army at the very start at the war and shrouded in secrecy as much as Katyusha rocket launchers. The soldiers who operated them not only had to be technically skilled to operate electric fuses, but also had to be well-trained and maintain a high level of discipline as they had to lie in ambush and keep their cool when the enemy advanced at them at a close distance, and would not be an exaggeration to call them part of the Red Army elite troops at the time. The success of 26th Independent Flamethrower Company was seen so important to the Soviet high command that on December 6 the Head of Chemical Troops of the Western Front Colonel Shalkov, Head of Chemical Department of the 5th Army Colonel Bregadze and the commander of the 2nd Flamethrower Platoon Lieutenant I. Shvets were summoned to meet Supreme Commander Joseph Stalin in the Kremlin. According to his secretary's log, Stalin had a conversation with them for 20 minutes, asking to detail him on the fights near Akulovo and Dyutkovo: how many tanks and infantry were destroyed and how flamethrower operators performed in battle. At the conclusion of this meeting Stalin said: "Flamethrower men did a great job. They should be awarded for this". Three officers: Bregadze, Kirichenko and Chernov, were awarded Orders of the Red Banner, four junior officers received Orders of the Red Star, and the 26th Independent Flamethrower Company was awarded an Honorific Red Banner. The Germans also appreciated the Soviet innovation, making a near exact copy of it - Abwehrflammenwerfer 42.

This battlefield site is part of my Battle of Moscow Tour